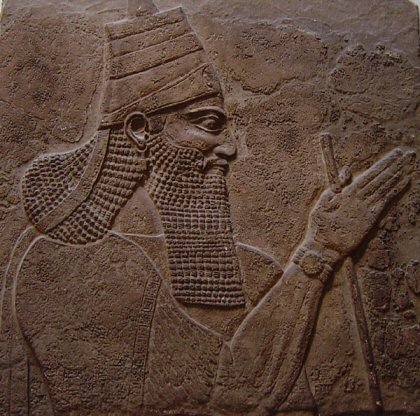

Figure 1. Tiglath Pileser III, probably during the Assyrian invasion of Israel, c. 733-732 BC

(750-500 BCE)

David Aberbach

London and New York

First published 1993

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

© 1993 David Aberbach

Typeset in Baskerville by Selwood Systems, Midsomer Norton

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner, Frome and London

All rights reserved.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

CONTENTS

List of illustrations ix

Preface x

Chronological table xii

Map xiv

INTRODUCTION 1

1. ASSYRIA AND THE FALL OF ISRAEL 19

Two Doom-Songs for Samaria 21

The Prostitution of Israel 23

Against Damascus 27

Song of a Vineyard 28

The Collapse of Israel 32

Tyre’s Fate 34

Against Philistia 36

Dirge for Moab 36

Oracles on Arabia 38

Poems to Egypt and Ethiopia 39

The Fall of Babylon 43

The Warning 45

Isaiah’s Poem to Sennacherib 47

The Restoration 50

2. BABYLONIA AND THE FALL OF JUDAH 53

The Age of Josiah’s Reforms 54

The Fall of Nineveh 56

Songs of God’s Injustice 59

The Battle of Carchemish 60

The Invasion 62

Nebuchadrezzar’s Attack 63

The Fate of Jehoiachin 65

Dirge for the Lions of Judah 66

Doom-Song for Egypt 68

Confessions of Jeremiah 70

Ezekiel: The Living Symbol 75

Lament for Judah 77

The Charge Against Edom 79

The Fall of Tyre 81

3. PERSIA AND JUDAH’S RESTORATION 87

Poems of Hope 87

The Fall of Babylon 90

Poem to Cyrus 93

Consolation 95

The Suffering Servant 99

The Stupidity of Idolatry 101

The Messiah 104

On the Warpath 105

The Day of Judgement 107

Bibliography 109

Index 114

ILLUSTRATIONS

All pictures reproduced by permission of the British Museum.

1. Tiglath Pileser III, probably during Assyrian invasion of Israel, c. 733-732 6

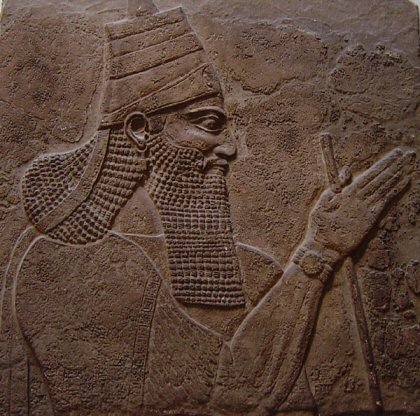

2. The siege of Lachish by Sennacherib, 701 9

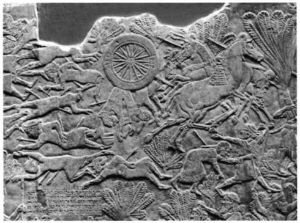

3. Lion killed by Assyrian king, c. 645 15

4. Jehu, king of Israel, pays tribute to the Assyrian king 19

5. Judean exiles from Lachish, 701 25

6. Assyrian attack on a river town, c. 865 30

7. Assyrian soldiers in pursuit of Arabs, c. 645 38

8. Nile sailing boat, c. 1800 41

9. Prisoners of war with Assyrian taskmaster, c. 700 49

10. Assyrian siege-engine in campaign in southern Iraq, c. 728 57

11. Scene of slaughter in Assyrian-Elamic wars, c. 663 61

12. Lion about to be killed, c. 645 67

13. Torture of Judean prisoners, Lachish, 701 79

14. Assyrian warship, probably built and manned by Phoenicians, c. 700 84

15. Demolition of a city in Assyrian-Elamic wars, c. 645 92

16. Ram-headed god of wood, Thebes, c. 1320 103

17. Assyrian king fighting lions, possible symbolic of his enemies, c. 645 105

PREFACE

This book has had a long germination and has been shaped by a number of people and experiences. Dr David Goldstein, late Keeper of Hebrew Books and Manuscripts in the British Library, first suggested to me in 1977, when I was a doctoral student at Oxford, that I try my hand at translating extracts from the prophets. For several years, working intermittently on these translations, I took part in a Hebrew Translation Workshop run by Dr Nicholas de Lange of Cambridge University. Many of the translations in this book were done with half an ear, as it were, for oral recitation in a relatively colloquial rhythmic style, this being close to the spirit of the Hebrew original - our habit of silent reading is, of course, relatively modern.

In the middle of this period, I finished my doctorate and spent two years (1980-2) as a trainee in child psychotherapy at the Tavistock Clinic. This training indirectly had a deep impact on my reading of the prophets. It stimulated much thought on the relationship between the inner life of the creative individual and external social and political reality. Translation led me to an increasing interest in the historical background of the Bible, and the prophets in particular. The frame of the present book, the last of several drafts, was determined by one observation: that each of the three surviving waves of prophecy appeared to coincide with a wave of imperial conquest in the Fertile Crescent.

This observation led me to sociology and religion and to a study of imperialism, including latterly a period as Academic Visitor in the Sociology Department of the London School of Economics, and the book in this way evolved from being an anthology of translations to an interpretation both of the relationship between political power and creativity and of the origins of Judaism.

The final draft of the book was written amid daily news of the collapse of the Soviet empire, when the Bible became the single best- selling book in the independent states. My feeling that the prophets were catching up with current events was increased when Iraq invaded Kuwait, precipitating the Gulf crisis of 1990-1. Iraq’s dictator, Saddam Hussein, declared his aim of emulating the great Assyrian and Babylonian conquerors, particularly Nebuchadrezzar. More recently, the forced population transfer (‘ethnic cleansing’) of Bosnian Moslems by the Serbs is the latest of countless examples of a policy invented by the Assyrians and used against both Israel and Judah in the time of the prophets.

The poems entitled ‘The Prostitution of Israel’, ‘Song of a Vineyard’, ‘The Fall of Nineveh’, ‘The Suffering Servant’ and ‘Confessions of Jeremiah’ were first published in the Jewish Chronicle Literary Supplement. All illustrations are reproduced by permission of the British Museum. Special thanks are due to the staff of Western Asiatic Antiquities, the British Museum, for their patient help in choosing the illustrations.

I am most grateful to my editors at Routledge, Richard Stoneman, Heather McCallum, Sue Bilton and Maria Stasiak, for their invaluable help in the final stages.

This book will always be associated in my mind with especially happy memories of its inception and its conclusion: for it began life (though I did not know it) around the time I met my wife, Mimi, in Oxford over 15 years ago, and it reached its end at the time of the birth of our daughters, Gabriella and Shulamit. Indeed, the proofs arrived virtually together with Shulamit!

Finally, I thank my students at The Leo Baeck College, London, and McGill University, Montreal, with whom many of the ideas in this book were first explored, as well as a number of scholars, some of whom have asked to remain anonymous, who read the book, or parts of it, in draft form and commented on it: Professors Robert Alter, Fred Halliday, Dan Jacobson, John Sawyer and Michael Weitzman, and my father, my first teacher, Professor Moshe Aberbach, to whom this book is affectionately dedicated.

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

c. 745-727 BC

Reign of Tiglath Pileser III. Assyria conquers most of the Fertile Crescent.

c. 740-700

Age of Isaiah. Hosea, Amos, Micah.

c. 734-732

War of Aram and Israel against Judah. Judah allies itself with Assyria. Israel is annexed by Assyria.

729 BC

Assyria conquers Babylonia.

c. 727-722

Shalmaneser V is king of Assyria.

c. 725-697

Hezekiah is king of Judah.

c. 724-721

Israel revolts against Assyria.

721 BC

Fall of Samaria, capital of Israel. End of kingdom of Israel. Exile of many of Israel’s inhabitants to Mesopotamia. Judah survives as a vassal state of Assyria.

721-705

Sargon II is king of Assyria.

721-710

Babylonia, led by Merodach Baladan, revolts against Assyria and is defeated.

705-681

Sennacherib is king of Assyria.

701 BC

Assyria crushes revolt involving Judah; besieges but does not capture Jerusalem.

c. 696-642

Manasseh is king of Judah.

681-669

Esarhaddon is king of Assyria.

669 - c. 633 BC

Ashurbanipal is king of Assyria.

c. 663 BC

Assyria conquers Egypt.

c. 640-609

Josiah is king of Judah. Collapse of Assyrian empire.

c. 630-570

Age of Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Zephaniah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Joel (?), Obadiah.

612 BC

Fall of Nineveh, Assyria’s capital, and disappearance of Assyria. Babylonia takes over the Assyrian empire.

609 BC

Battle at Megiddo between Judah and Egypt. Josiah is killed.

605 BC

Battle of Carchemish. Egypt is defeated by Babylonia under generalship of Nebuchadrezzar. Judah becomes a vassal state of Babylonia.

605-562 BC

Nebuchadrezzar is king of Babylonia.

c. 602-597

Judean revolt under Jehoiakim is defeated, Jerusalem is captured, and many of Judah’s inhabitants are exiled to Babylonia.

c. 590-586

Judean-Egyptian revolt fails, Jerusalem is destroyed by Nebuchadrezzar, the Temple is burned down, and many more Judeans are exiled.

539 BC

Conquest of Babylon, Babylonia’s capital, by Cyrus, king of Persia. Persia takes over the Babylonian Empire.

c. 539-516

Age of Second Isaiah. Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi.

538 BC

Cyrus’ Edict of Liberation allows exiled Judeans to return home.

c. 516 BC

Consecration of Second Temple in Jerusalem.

INTRODUCTION

The poetry of the biblical prophets is inseparable from the empires which determined the history of the ancient Near East and the fate of Israel and Judah from the late eighth century to the end of the sixth century BCE * - first Assyria, then Babylonia and finally Persia. Each empire had its own character and motives and stimulated a distinct wave of prophecy, led by Isaiah ben Amoz during the Assyrian heyday, by Jeremiah and Ezekiel at the time of Babylonian supremacy and by Second Isaiah (the anonymous poetry appended to the book of Isaiah) during the rise of Persian hegemony. While prophecy was not confined to Israel, the phenomenon of prophetic poetry as it developed in Israel was unique and without a real parallel elsewhere. 1 It is one of the outstanding creative achievements in literary history and its impact on civilization is incalculable. It represents the triumph of the spiritual empire over the mortal empire; of the invisible God, king of the universe, over the human king of the civilized world; of losers over victors; of moral ideas over military force; and also, in a sense, of the creative imagination over historical facts. It is the only surviving body of poetry from the ancient Near East which, for the most part, belongs to a clearly defined historical period - though it aims in effect to extricate itself from history - 750-500 BCE being the period marking the rise of the Assyrian empire until the restoration of the exiled Judeans to their land from Babylonia.

Although this poetry was written (or spoken) largely in response to the rise and fall of the Assyrian and Babylonian empires, it gives an extremely sketchy and misleading picture of the period. Judging from the prophets, Israel and Judah were central powers of the Fertile Crescent, equal in might and influence not just to the surrounding

_______________

* All dates referred to are BCE.

nations - Edom, Moab, Ammon, Philistia, Aram and Phoenicia - but also to the Mesopotamian nations which posed a constant threat. The fall of the kingdom of Israel around 720 and of Judah just over a century later did not occur because they were tiny, mostly insignificant pawns in the politics and economics of the region. Their defeats were not inevitable consequences of military weakness, of geographic vulnerability, of unavoidably inferior manpower and resources. They fell because of moral backsliding: had they retained their faith in God and observed the Law, the prophets imply, they would have been victorious.

Historically (though not theologically), this biblical picture distorts the facts, as archaeologists and biblical scholars have discovered in the past 150 years. Assyria, by the late eighth century, had built the most powerful empire in history to date, over a hundred times larger than Judah, with the vast majority of the population in the Near East under its rule. It had the strongest army ever to be assembled and pioneered revolutionary techniques of warfare, for example in the use of cavalry and the implements of siege - these would be used for the next two and a half millennia. Its success was owed not just to its military power but also to a highly effective bureaucracy based in Assyria, with a network of administration and trade stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Egyptian border (by 663 the Assyrians had conquered Egypt, thus gaining control of the entire Fertile Crescent). In addition, Mesopotamia had a sophisticated civilization, was a leader in many of the arts and sciences and had an elaborate polytheistic religion with a remarkable mythology, traces of which survive in the Bible, especially in the opening chapters of the book of Genesis.

The true character and might of Mesopotamia do not emerge in the prophets. Assyria and Babylonia (like Persia after them) are depicted at best as agents of God’s will, commanded to punish Israel and Judah for their sins, and at worst as tyrants and idol-worshippers doomed to extinction. And this image of the ancient empires came down in history because the Bible survived while Assyria and Babylonia vanished virtually without a trace, their superb temples and palaces, their art and literature, their language, buried and obliterated. Whereas Jerusalem has been inhabited by Jews during most of its 3,000-year history from biblical times until the present, the great capitals of Mesopotamia - Asshur, Calah, Khorsabad, Nineveh, Babylon - were so completely forgotten that their very sites were for the most part unknown prior to the nineteenth century. While Hebrew was venerated and studied as the word of God, Akkadian, the cuneiform language of Mesopotamia, was lost for well over 1,500 years and deciphered only in the mid-nineteenth century.

If the Bible grossly misrepresents Mesopotamia, the hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets recovered in archaeological digs over the past 150 years yield little insight into the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. 2 These kingdoms are mentioned rarely, almost invariably as minor participants in extensive military campaigns or swallowed up in long lists of nations forced to pay tribute. While some biblical kings appear - Jehu, Ahaz and Hezekiah among them - no other biblical character, not even Isaiah ben Amoz or Jeremiah, has yet been identified in Mesopotamian writings. The destruction of the two kingdoms is given brief mention. The fact that they were, according to the Bible, a unique monotheistic enclave (albeit a flawed monotheism) in a polytheistic world is passed over in silence. The extraordinary characters and literature of the Bible left no known mark on Mesopotamian culture.

However, in their most brilliant creative achievements, Mesopotamian and Israelite cultures were not dissimilar: the toughness, violence and emotiveness of prophetic poetry have their visual counterpart in the magnificent wall reliefs of war scenes and lion hunts which hung in the palaces of the Assyrian kings. The prophets rarely condemn the Mesopotamian empires for their barbarity - for flaying their enemies alive, chaining them in cages, immuring them, cutting out their tongues and eyes, cutting off their genitals and feeding them to dogs, burning, impaling, piling up their heads or corpses, as depicted in their inscriptions. Violence and cruelty were part of the biblical world, and we may take passages from poems attributed to Moses and Deborah - both are described as prophets - to point out the violent thrust of biblical poetry. In the ‘Song of Moses’ (Deuteronomy 32), a bloodthirsty Yahweh thunders at his people for turning after strange gods of wood and stone, this being a frequent motif in prophetic invective: 3

I will make my arrows drunk

with the blood of captive and slain!

My flesh-devouring sword

on the heads of the wild-haired foe!

If these lines were spoken not by God but by an Assyrian conqueror - Shalmaneser III or Sargon II, for example - they would be equally, if not more, convincing as the outburst of a king believed to have the authority of a god.

The ‘Song of Deborah’ (Judges 5), likewise, illustrates several features of the prophetic style, particularly in the rhetoric, the repetition, the imagery and the intense rhythmic excitement of Deborah’s victory over the Canaanites:

The kings came and fought.

The kings of Canaan fought in Ta’anach

by the waters of Megiddo -

no silver spoil for them!

The heavens fought,

the stars fought Sisera in their orbits,

the river Kishon swept them away,

ancient river, river Kishon . . .

Here again, the triumphant mood is not unlike that in Assyrian art, the Lachish reliefs for example, and also, occasionally, in the annals of the kings. The touching vignette of Sisera’s mother at the close of the poem also recalls the Assyrian engravings of their enemies in defeat and exile.

Each of the surviving three major waves of Hebrew prophecy came about in wartime, and war is the subject of, or background to, most of the prophetic poetry, even that depicting the golden age at the end of days when swords are beaten into ploughshares and the wolf lies down with the lamb: at that time Israel and Judah will gain resounding victories over their enemies (Isaiah 11). Only then will God be ‘king of the whole earth’ (Zechariah 14:9), an image of imperial rule deeply influenced, no doubt, by the Mesopotamian kings who used an identical phrase to describe the extent of their power (e.g. Pritchard, p. 297). 4

Thus, by identifying itself with a spiritual empire, an immortal kingdom of God mirroring and rivalling Mesopotamian kingdoms with their feet of clay, Judah stretched the range of creative imagination and in doing so held on to its unique identity even, and perhaps especially, in exile.

While the prophets extol the virtues of submission, justice, kindness and mercy, their strongest moods are of angry defiance, accusation and bitter guilt; and this might be explained in the context of imperial expansion in the 200 years starting from the mid-eighth century. It cannot be accidental that the first extant written prophecies - of Isaiah ben Amoz, Hosea, Amos and Micah - coincide with an astounding series of Assyrian conquests in the second half of the eighth century. During that time, hardly a year passed without a military campaign. The cataclysmic effect of these wars of expansion may be gauged in Isaiah’s impassioned prophecies to surrounding nations - Egypt, Ethiopia, Arabia, Aram, Edom, Moab, Phoenicia, Philistia, as well as Assyria and Babylonia. These prophecies barely acknowledge Assyria as the main cause of upheaval, perhaps because this was self-evident or as a slap at Assyria by attributing its victories not to its superior power but to God. The prophecies to the nations in Isaiah and later prophets, Jeremiah and Ezekiel particularly - there are about three dozen such prophecies in all - chart the course and impact of imperial expansion and give a unique outsider’s view of the great events of the age. The threat of being overrun and the experience of vassaldom were among the most powerful spurs bringing about an explosion of creativity in Judah starting from the mid-eighth century. Prophecy served to control and make sense of otherwise uncontrollable, incomprehensible, earth-shaking events, to create something of permanent theological and aesthetic value in the face of impending disaster.

To explore the meaning of this simultaneous growth of empire and prophecy, it is useful first to outline the extent of the Assyrian conquests and to offer some interpretation of Assyrian imperialism in the light of modern theories.

Tiglath Pileser III, a general who usurped the throne around 745, was chiefly responsible for Assyria’s rise as the first extended empire in history: he conquered most of the Fertile Crescent, made the northern and eastern borders safe from marauding tribes, and divided the territory into administrative units designed to protect the trade routes and to collect taxes with maximum ease. To these ends, he built a network of roads - the finest prior to the Romans - together with a chain of resting posts and forts. To ensure the disorientation of his defeated enemies, to make use of them and, finally, to assimilate them into Assyrian cities, he instituted a policy of deportation to the Mesopotamian heartland where the exiles were put to work on public building projects. As we shall see, this policy inadvertently had momentous consequences for civilization as it broke down ethnic barriers and

opened the way for the future extension of prophetic influence and of Judaism (and through Judaism, Hellenism and, later, Christianity and Islam) as a universal religion. But at the time, deportation was a catastrophe: Israel was exiled by the Assyrians and Judah by the Babylonians, and this policy was reversed only by the Persians in the late sixth century. The over-extension of the Assyrian empire, civil war in the time of Ashurbanipal and the natural hatred engendered by a tyrannical regime, weakened the empire. In the late seventh century it collapsed and disappeared.

The phenomenon of Assyrian imperialism is crucial in the poetry of the prophets. Why did the Assyrians build their empire? Why did it fall, while Judah, for all its insignificance, survived? Interpretations of imperialism have originated mostly since the late nineteenth century, based upon studies of modern empires. 5 The word ‘imperialism’ was originally used specifically to describe modern, not ancient, empires, and there is a view among some scholars that it should be confined to modern empires. However, scholars specializing in ancient Mesopotamian kingdoms agree almost unanimously that the word is applicable also to Assyria, Babylonia and Persia in the prophetic age, inasmuch as the human forces underlying imperialism have not changed greatly and its means and ends remain fundamentally the same.

Historical and theoretical evidence suggests that imperialism results from diverse factors: nationalism and economic pressure; the drive for power and prestige; greed, cruelty and raw energy; the struggle for security; and surprisingly, even humanitarianism and a desire to enlighten. Among these and other forces, the ones most obviously applicable to Mesopotamia are geography and economics, though religious motives are stressed in the ancient inscriptions (‘The God Asshur, My Lord, commanded me to march . . .’). Geographically, Assyria had no clearly-defined borders: it was surrounded on all sides by often hostile nations and tribes. While it had much fertile land by the Tigris and its tributaries, which attracted invaders, Assyria had few raw materials and had to import wood, stone, bronze, copper, wool, flax and, above all, iron. (This economic reality may have influenced the Mesopotamian worship of idols of wood and stone, which the prophets mock and condemn ceaselessly - such commodities, plentiful to the Judeans, were precious to the Assyrians.) A further destabilizing factor was the irregular rise and fall of the Tigris and Euphrates, which could lead to inadequate irrigation one year and flooding the next, and which required an elaborate and not always effective network of dykes and canals. These conditions forced Assyria to maintain a strong army and to look beyond its borders, especially to the Mediterranean coast, for raw materials. The eighth century was a time of expanding Mediterranean trade, and one of Tiglath Pileser III’s chief military feats was the conquest of the east Mediterranean coast, with its trade routes and ports. His successors, Shalmaneser V, Sargon II, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, were largely successful in consolidating the empire and maintaining control over trade from Egypt to Persia and northwards to the Taurus mountains. The growth of international trade increased the strategic importance of Israel and Judah, straddling the land bridge between Asia and Africa, and for this reason the prophets were not entirely exaggerating in speaking of their land as central.

The picture of Assyria as the wolf come down on the sheep in the fold has blocked the impartial assessment of its campaigns for territorial expansion in the eighth century. To the sociologist Joseph A. Schumpeter, Assyrian imperialism was a sport, motivated by the basest instincts which are never entirely absent in modern imperialism (or, for that matter, in human nature) - bloodlust, greed, power-hunger, sadism and perverted sexuality: ‘Foreign peoples were the favourite game and toward them the hunter’s zeal assumed the forms of bitter national hatred and religious fanaticism. War and conquest were not means but ends. They were brutal, stark naked imperialism . . .’ 6

Only in recent years, through evidence discovered in cuneiform, have scholars begun to regard Assyrian imperialism with any sympathy.

One historian, H.W. Saggs, has admitted that he actually likes the Assyrians and has suggested that, but for Assyria, Judah and Judaism might not have survived:

Imperialism is not necessarily wrong: there are circumstances in which it may be both morally right and necessary. Such was the case in the Near East in the early first millennium. But for the Assyrian Empire the whole of the achievements of the previous 2000 years might have been lost in anarchy, as a host of tiny kingdoms (like Israel, Judah and Moab) played at war amongst themselves, or it might have been swamped under hordes of the savage peoples who were constantly attempting to push southwards from beyond the Caucasus. 7

It is hard to see Tiglath Pileser III, Sargon II or Sennacherib as an unwitting saviour of Judah, but there is reason to believe that this was so. For in a sense, Assyrian imperialism forced upon Judah the discipline of monotheism and its teachers, the prophets. If left alone, Judah might have abandoned its faith and submitted to the paganism which dominated the Near East, making it far more vulnerable to assimilation and disappearance.

The discovery of the uses of iron - the greatest technological advance of the biblical era - made possible the type of imperialism created by Assyria as well as the defences against imperialism, the military ones and also, indirectly, the spiritual ones of the prophets. The Assyrians were the first to create a large iron weapons industry, and through the mass production of iron weapons put these instruments of destruction for the first time into the hands of sizeable armies. Iron changed forever the nature of warfare, travel and trade, all crucial to imperialism. The phenomenal Assyrian military successes of the late eighth century, news of which came to Europe via the Greek trading posts in the east Mediterranean, accelerated the growth of an iron-based urban economy in Europe, paving the way for the rise of the Greek and Roman empires. Assyrian improvements in the design of the bow, the quiver, the shield, body armour and the chariot (making it heavier, strengthening the wheels), as well as increasingly effective battering rams to penetrate siege walls and city gates, were largely made possible by iron tools and materials. Iron played its part in military training and combat techniques, in the building of roads and new means of rapid, flexible deployment of troops, logistics and administration. The poetry of the prophets echoes with iron: soldiers on the march, horses galloping, the glint of javelins, the thrust of swords, the clang of chariots.

While Assyria built the finest offensive army in history to date, Israel and Judah and other nations in the Near East developed some of the most sophisticated means of defence: walls, siege fortifications, gates, towers and protective structures on the walls, and engineering, notably Hezekiah’s five-hundred-metre conduit hacked through the rock from the stream of Gihon into the city of Jerusalem. 8 Jerusalem was never conquered by the Assyrians, and Samaria, which in some places had walls thirty-three feet thick, resisted Assyrian siege for three years.

[Figure 2. The siege of Lachish by Sennacherib, 701 BC]

The prophets were part of these defences, strengthening resolve against the moral ‘breach in the wall’ (Isaiah 30:13), depicting God as the only king and warrior-protector - ‘shield’, ‘wall’, ‘bow-man’, ‘chariot-driver’ as well as a type of smith-creator, removing impurities, battering the heart of his people into new shape, using the prophets as tools and fortifications. The prophet Jeremiah, for example, is chosen by God to be a ‘bronze wall’, an ‘iron pillar’ and a ‘walled city’ protecting the faithful (Jeremiah 1:18, 15:20). Significant, too, is other prophetic imagery of iron: the iron axe wielded by God in leading the Assyrians to victory over his faithless people (Isaiah 10:34), the iron yoke made by God to symbolize the supremacy of Nebuchadrezzar (Jeremiah 28:14), the iron pen to inscribe the sins of Judah (ibid. 17:1). At the same time, the prophets denigrate the uses of iron in war as in idol-worship, and the iron-smith is a target of the most vituperative mockery in Second Isaiah.

While Assyria’s imperial growth stiffened Judah’s will to survive, it also led to the destruction of Assyria within a century. The cruel force needed to build and sustain the empire aroused violent hatred throughout the Fertile Crescent; it died, as Napoleon put it, of indigestion. Demographically weak, Assyria could not hold down its huge empire. At virtually every opportunity, the subject nations, who provided much of the Assyrian military and administrative manpower, rebelled. Power was so centralized that the death of the king, who was believed to have divine authority, weakened the empire still further and often provided the best conditions for revolt. The seismic effects of the deaths of Assyrian kings are among the main events of the century preceding the annihilation of Assyria, and they decisively influenced the growth and character of prophetic poetry. After the death of Tiglath Pileser III in 727, Israel rebelled and was crushed and exiled. Against the background of revolt in the western provinces of the empire, Babylonia followed suit and waged a long and initially successful war against Assyria after the death of Shalmaneser V in 722. The death of Sargon in 705 led to widespread revolt in both the eastern and western sides of the empire. The death of Sennacherib in 689 again set off unrest which Assyria this time managed to contain rapidly. The death of Esarhaddon in 669 brought civil war and wars with Babylonia and Egypt. And finally, the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 triggered a massive revolt and the collapse and disappearance of Assyria.

The prophets’ response to Assyria was inherently ambivalent. On the one hand, Assyria was hated and feared as the piratical empire that had crushed Israel and came within a hairbreadth of doing the same to Judah. This empire had an enviably attractive polytheistic culture, needing little or no military coercion to impose it on subject nations: the people of Israel, for example, seem to have assimilated willingly, though they had fought hard to keep their independence, and their kingdom and faith were lost in exile. On the other hand, if monotheistic faith was to survive, the Judeans had to learn to accept Assyrian victory as the will of God. This may be why no extended prophecies against Assyria are found in the period of its greatest military successes. Isaiah has no ‘burden of Asshur’, neither does Micah or Hosea; and the prophecies against the nations which start the book of Amos do not include Assyria. The vivid memory of Israel’s exile challenged the prophets: how to maintain a monotheistic faith strong enough to keep alive a national-religious identity in exile as well as the hope of return. The lack of unity which had led to Israel’s split into two kingdoms in the tenth century was another force which, paradoxically, helped Judah to survive. For after Israel’s fall, Judah had over a century to ready itself psychologically for the possibility of exile, to avoid being swallowed up like Israel. The threat of exile concentrates a nation’s mind wonderfully, and the prophets’ writings are the full creative flowering of this concentration.

The prophets, then, were leaders in a war against cultural imperialism, and perhaps this was initially the main reason for the writing and preservation of their teachings. Though they accepted submission to the superior military power as a condition of survival, they subverted imperial rule in a number of ways: in their attacks on the materialism and injustice which were inevitable consequences of imperialism; in their apparent lack of concern with economic realities, which may be seen as a backhanded attack on the very foundation of Assyrian expansionism; in their insistence that the divine word was not the monopoly of priest and king in the sanctuary, but could inspire the common man, even a shepherd such as Amos; in their undying hope for the ingathering of exiles, which ran directly counter to Assyrian policy; in their readiness to admit defeat, to depict it graphically and to accept it as the will of God; in maintaining belief in one omnipotent God in opposition to what they saw as the paltry polytheism of Mesopotamia. ‘The prophetic ideal’, writes Yehezkel Kaufmann, ‘was the kingdom of God, the kingdom of righteousness and justice. This was the basis of the first Isaiah’s negation of war and of dominion acquired by warfare. This ideal implied the negation of world rule generally, of empire . . .’ 9 The unique ferocity of the prophets’ attacks on idols and idol-worship, while largely ignoring the rich mythology of pagan beliefs, may have been less a sign of hatred for idol-worship per se than of the empires which were odiously identified with the false gods and the magic and superstition associated with them.

The late-eighth-century prophets were torn between detestation, hatred and fear of Assyria and identification with Assyria as the rod of God’s wrath. Consequently, their hatred of Assyria was shunted to a large extent onto various targets: idols, idol-worshipping nations and Judeans who failed in moral self-discipline. But only with the fall of Assyria could this hatred burst out freely and without terror of reprisal. Loathing and fear of Assyrian tyranny are spelt out in the relish and glee with which the prophet Nahum depicts the fall of Nineveh and of the Assyrian Empire. 10

During the most stable period of the Empire, from the middle of Sennacherib’s rule until the death of Ashurbanipal, from about 700 to 627, there is no datable Hebrew prophecy. It is likely that Hebrew prophecy was suppressed, perhaps even by royal command, during this period. Manasseh, the Judean king for much of this time, reportedly spilt much blood, and the prophets might have been among his victims.

With the collapse of Assyria, Hebrew prophecy re-emerged and entered its second great period, against the background of Babylonian and Egyptian rivalry and the defeat and exile of Judah by the Babylonians. For a short time at the end of the seventh century, Judah seemed within reach of independence, but with the defeat of Josiah by Egypt in 609, it reverted to vassaldom. The motif of God’s injustice - why do the righteous suffer and the wicked prosper? - emerges in prophetic poetry at this time, as if in response to the failure to gain independence at a time of the breaking of nations. The Babylonian defeat of Egypt at Carchemish in 605 was a watershed which left a strong mark upon prophetic poetry. With this victory, Babylonia took over the mantle of imperial conqueror left by Assyria. As in the previous century, Judah was caught up in the jockeying for power of Egypt and Mesopotamia, the prophets warning against alliances, especially with Egypt, which could lead to disaster. Jeremiah was jailed in besieged Jerusalem for his pro-Babylonian views and let go only after Nebuchadrezzar defeated Judah, burned down the Temple in Jerusalem and exiled most of its inhabitants.

Had the Babylonian empire survived for a century or two rather than a half-century, the Judean exiles might have assimilated into Babylonian society as the Israelites had in Assyria. The rise of the Persian empire saved Judah and, in effect, made possible the survival and growth of Judaism. Following his defeat of Babylon in 539, the Persian king Cyrus issued an edict allowing the Jews exiled by the Babylonians to go back to their homes in Judah. This act stimulated the third and final wave of biblical prophecy, dominated by Second Isaiah, which for the first time conveys the ecstasy of vindication, of having come through, the sheer relief of regaining the territorial homeland, and the gratitude to God and commitment to his Law.

The Jews, having survived, alone, as it turned out, among the peoples of the ancient world, felt an enormous sense of privilege, specialness, responsibility and chosenness. In the course of a single lifetime, the two most powerful empires in history, Assyria and Babylonia, had disappeared, while Judah miraculously held on. From the ecstatic viewpoint of Second Isaiah and his contemporaries, the earlier prophets such as Isaiah and Jeremiah had been proved right: faith in the end was indeed stronger than military force. And so, in their desperate search for defences against imperialism, the prophets discovered an alternative to empire which became the basis of Judaism in exile and, later, of Christianity and Islam. Faith is independent of time and place - this was their discovery - and they prepared the way for what Isaiah Berlin called ‘a culture on wheels’, a mobile culture built upon faith and viable in exile.

It is striking in the biblical account how the weakening of imperial rule both in the late eighth century and the late seventh century was accompanied by a turning back to Yahweh-worship and the destruction of idols, and how the discovery of the Book of the Law (believed to be Deuteronomy) occurred just when Assyria lost its military grip at the end of the seventh century. Most of the main elements of Judaism in exile appear to have crystallized into a religious way of life under Persian rule, at the tail-end of the prophetic period (the prophets vanished, one feels, because their task was done): belief in one invisible universal God and the total rejection of idols and magic; attachment to the memory of the Land of Israel; the introduction of synagogue worship as a substitute for Temple worship, and of prayer and study in place of the sacrifices; the repudiation of intermarriage; the invention of proselytization, this being almost a religious warfare equivalent to imperialism, and of the idea of martyrdom to defend the faith (as suggested in the book of Daniel which, although written much later, describes the Persian period), as well as the concept of the Messiah who would appear at the end of days and restore the Davidic kingdom of Judah. As indicated earlier, the exposure of the exiled Judeans to a kaleidoscopic group of other exiled peoples inclined them to develop their religion along far more universalistic lines than would have been possible in Judah. At the same time, the alienation and aggressiveness of some of the exiles gave rise to hatred, which was to develop into full-blown anti-Semitism during the Hellenistic period and onward.

The modern reader confronted with prophetic poetry for the first time might find it confused and bewildering in its fragmentation; unsettling in its violence, sentimentality and humourlessness; tendentious, arrogant, presumptuous and even mad in speaking in God’s name; professing a universality which it does not necessarily have; a timebound phenomenon foisted on to later generations as an absolute, unchanging truth for all time. Yet if poetry is judged by its power to inspire, to change people’s lives, their way of looking at things, Hebrew prophetic poetry is the most influential body of poetry in history. Every political and religious movement which stresses the value of social justice and compassion, opposes materialism and the unjust distribution of wealth, objects to ritual at the expense of spirituality and to the emphasis on the letter of the law rather than its spirit, and fights the abuse of power, owes something to the prophets. There is a view which extends prophetic influence even further: by freeing the world from magic, the prophets created the basis for modern science and technology and for capitalism. 11 However, from a creative standpoint the prophets’ impact is most striking: all poets who write religious or political poetry, or in a rhetorical, confessional or lyrical mode are part of a tradition in which the prophets are among the prime movers, their taut, rhythmic, gritty Hebrew rich in imagery, contrasts and emotional range, of anger and tenderness, devastation and hope, vision and sarcasm.

The prophets, above all, helped transform Judaism from a national and parochial religion to a universal one, progenitor of Christianity and Islam. For all its bitterness, their poetry is remarkably hopeful and life-affirming, coming as it does from a people under constant threat of annihilation, whereas the outstanding Mesopotamian art is possessed by death. Death is the main subject of the finest poem of this civilization, the epic of Gilgamesh, which ends with Gilgamesh awaiting death by the magnificent city walls which he has built. Gilgamesh weeps to Urshanabi, the ferryman across the waters of death: ‘O Urshanabi, was it for this that I toiled with my hands, is it for this that I have wrung out my heart’s blood? For myself I have gained nothing . . .’ 12 The most memorable representations in Assyrian art - the lions caged and trapped, pierced by arrows and spears, convulsed in dying agonies - may be taken in the end as a symbol of empire, violent and unloved, lacking spiritual direction, turning upon itself in a Götterdämmerung of despair.

The relevance of the prophets today lies not just in their religious and social message and their aesthetic attraction, but also in their condemnation of the greed and cruelty of imperialism and their creation of a spiritual alternative. This book aims, accordingly, to be an

[Figure 3. Lion killed by Assyrian king, c. 645 BC]

interpretative history and anthology of prophetic poetry through each of the three major imperialistic periods - Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian. About three dozen outstanding poems and fragments are arranged in a running narrative starting from the late eighth century until the late sixth century. Though precise dating is rarely, if ever, conclusive and the authorship of many passages is in doubt - the nature of the problem may be appreciated by comparing Isaiah 2:1-4 and Micah 4:1-3 - prophetic poetry encourages a limited historical approach: the prophets often respond directly to specific events, and in many cases, such as Isaiah’s poem to Sennacherib, Nahum on Nineveh’s fall, Jeremiah on the battle of Carchemish, or Ezekiel’s allegory on the lions of Judah, the dating of the poetry is fairly clear, and is often stated in superscriptions. (In some instances, Ezekiel gives the exact year, month and day of a particular vision, though he does not say how much time passed before it was written.) By reading in a loose chronological order these and other poems datable within a rough period (such as Isaiah’s oracles to the nations), a vivid, idiosyncratic portrait emerges of the main events and changes in the Near East of the eighth to the sixth centuries.

The treatment of the prophetic books as anthologies of poems and fragments is justified by scholarly consensus. John Bright writes: ‘The Book of Jeremiah, like most of the prophetic books, is a kind of anthology - or, to be more accurate, an anthology of anthologies - and is to be read as such.’ 13 To my knowledge, no such anthology of prophetic poetry has been done before. In fact, it is rare for these texts to be translated not by a committee or by authority of a committee, but above all as ancient poetry written or spoken in its time by men speaking to men and aiming at freshness, clarity, rhythm, power of expression and influence.

In any attempt to enter the world of the prophets, frustration in the end surpasses curiosity, the mystery overwhelms the sum of the facts. The poetry quivers with tantalizing questions, and it is well to conclude this introduction by giving an idea of our ignorance. So much has been written on the fifteen books of the literary prophets, which total just a few hundred pages in the Hebrew Bible - literally tens of thousands of books and editions - that one might think that a great deal is known. The opposite is true: so much has been written because so little is known. Our ignorance is betrayed in the following questions, a few among many which have no answer and are not likely ever to be answered fully: did the prophets visit Assyria or other countries which enter their poetry? Did they have any contact with other prophets in the Near East? Did any of them know Akkadian and, if so, how did this affect their prophecies? Did they write much that has been lost? Was there a written prophetic tradition prior to the age of Isaiah which has been lost? Did the ‘false prophets’ make written prophecies? If so, what was their literary merit and influence and what happened to them? Who were the audiences of the prophets and how widely were they and their message known? How did they live their daily lives? Were their prophecies ever set to music? How were their works edited? Who were the prophets?

_________________

NOTES

1. John Bright (ed. and tr.), Jeremiah, The Anchor Bible, vol. 21, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1965, p. xix.

2. For a selection of some of the most important of these documents, see D. Winton Thomas (ed.), Documents from Old Testament Times, London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1958; and James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd edn, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. Henceforth referred to as ‘Thomas’ and ‘Pritchard’ in the text.

3. Translations are by David Aberbach. Sources of poems translated are given after each poem and refer to chapter and verse of the Hebrew Bible.

4. ‘Amid the clamour of the multi-racial metropolis [Babylon in the sixth century BCE] the exiles must have watched the kings of many nations bring their tribute to Nebuchadrezzar and have envisaged the long-promised Day

when the same would be done not for a man but for their God as King of Kings in his new city.’

(D.J. Wiseman, Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 115)

5. For bibliography on imperialism, see p. 113 below.

6. Joseph A. Schumpeter, Imperialism and Social Classes, tr. Heinz Norden, ed. Paul M. Sweezy, Oxford: Blackwell, 1951, p. 44.

7. H.W. Saggs, Everyday Life in Babylonia and Assyria, London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1965, p. 118.

8. See Yigael Yadin, The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands in the Light of Archaeological Study, 2 vols, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1963.

9. Yehezkel Kaufmann, History of the Religion of Israel, vol. IV, The Babylonian Captivity and Deutero-Isaiah, tr. M. Greenberg, New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1970, p. 117.

10. See pp. 56-8 below.

11. Cf. Max Weber, General Economic History, tr. Frank H. Knight, New York: Collier Books, 1961 (first published 1923), p. 265.

12. The Epic of Gilgamesh, tr. N.K. Sanders, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1960, p. 114.

13. Bright, Jeremiah, p. lxxix.

1

ASSYRIA AND THE FALL OF ISRAEL

[Figure 4. Jehu, king of Israel, pays tribute to the Assyrian king]

The above is the only extant contemporary picture of a biblical character. It appears on the mid-ninth-century Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III: the Israelite king, Jehu (or his messenger), is on his knees with gifts of gold and silver for the ‘Great Dragon’, the Assyrian king (Pritchard, pp. 276, 281). This is the same wild, violent, heroic Jehu of II Kings, anointed dramatically by the prophet Elisha, assassin of the kings of Israel and Judah, of Jezebel and Ahab’s seventy sons. Through Assyrian eyes, however, Jehu was nothing more than a cringing vassal. This image of prostration held true of Israel and Judah for the better part of the next two centuries, up to the fall of Nineveh in 612. Much of the political and prophetic activity in Israel and Judah during the century prior to the conquests of Tiglath Pileser III was in reaction to such humiliation and to further menace both from Assyria and Aram.

The ninth-century Israelite alliance with Phoenicia, for example, was an attempt to form a military bloc to fend off mutual enemies. Likewise, Israel’s peace with Judah, for the first time since the kingdom had split a century earlier, was precipitated by the threat from the north-east. At this time, too, the prophet Elijah, with Jehu’s help, and his disciple Elisha did away with the Canaanite prophets and the Baal cult and established the Yahweh cult as the major religious force in Israel. The recognition that the God of Israel and Judah could not compete militarily with imperial might is implicit in Elijah’s vision on Mount Sinai of the invisible God, speaking not with the fire and thunder of battle, but with the soundless voice of truth and justice.

Still, no written prophecies survived from the time of Elijah, and the Bible tells nothing of Assyria prior to the eighth century. Assyrian records show, however, that Aram and Israel fought a major battle against Assyria at Qarkar around 853 and apparently stopped the Assyrian army (Pritchard, pp. 276ff.). About a decade later, Aram attacked Israel and it seems that Jehu paid the Assyrians to halt the Arameans. During a brief period of Assyrian weakness, Aram overran much of Israel and Judah, but by the end of the ninth century Assyria recovered and fought a short, decisive war against Aram. With the defeat of Aram, the lost territories were regained and the military threat was temporarily lifted. The first half of the eighth century was a time of rare security and prosperity both for Israel and Judah.

The literary prophets, and the earliest firmly datable poetry in Hebrew, emerged at the end of this period of revival, when the Assyrians began the wars which led to their conquest of the Fertile Crescent by the end of the eighth century. The works of four prophets have survived from this time: Amos, Hosea, Isaiah and Micah. All, except probably Hosea, were Judeans and all, with the possible exception of Micah, were born in the time of relative peace and economic boom which had made Israel and Judah together as powerful as during David’s heyday. By the time of their deaths, Judah was a vassal of the Assyrians and Israel was wiped off the map. The prophets were obsessed with the question of morality and retribution: if Yahweh was omnipotent and, indeed, the God of the nations as well as of Israel and Judah, how could he allow the fall of his people? They could admit only one answer: prosperity had led to social injustice and moral laxity. Israel was punished for its sins by the Assyrians, the rod of God’s wrath, as Isaiah (10:5) describes them. And so, the prophets castigate Israel and Judah. Everywhere they saw moral decline leading to corruption and disaster. In the books of Amos and Isaiah, for example, the ignoble aristocrats of Israel (=Jacob) debauch themselves in the capital city of Samaria as military disaster threatened.

TWO DOOM-SONGS FOR SAMARIA

1

You alone have I known

among the families of men:

Therefore I will punish you for your sins!

Hoi!

Uncaring in Zion!

Safe on Samaria’s mount!

Aristocrats ruling Israel!

Go to Calneh’s ruins,

of Hamath Rabbah,

of Philistine Gath down south:

Are you better than they?

Is their border longer than yours?

You put off the bad day,

bring violence closer.

You sprawl across your ivory beds.

You eat fresh lamb and calf.

You pluck the harpstrings,

Davids the lot of you!

drinking wine from bowls,

using the best oils!

You care nothing for your country’s grief!

So - you’ll be first into exile,

your stinking orgies will stop -

For I abhor Jacob’s arrogance,

I hate his palaces.

I will cut this city off!

great house and small alike,

smash to splinters -

Can horses run on rocks?

or oxen plough the sea?

But you - you’ve made justice poison,

and righteousness bitter fruit.

You’re happy - for no reason:

‘We muscled our way to power!’

Now I, Yahweh God of the Hosts, say:

I will raise against you,

House of Israel,

a nation to squeeze you

from Hamath up north

down to the plains of the Dead Sea!

Are you different from the Ethiopians,

children of Israel?

For though I took Israel from Egypt

I did the same for the Philistines from Cyprus

and Aram from Kir!

The eyes of the Lord

are fixed on the kingdom of sin:

I will annihilate it . . .

2

Hoi!

Arrogant crown of Israel’s drunks,

fading wreath to its glorious beauty

which crowns the valley of fat -

its wine-stunned rulers!

Look!

The power of the Lord

will stream like hail, a killer-storm

flooding the earth with force.

The arrogant crown of Israel’s drunks

will be crushed underfoot,

and the fading wreath of its glorious beauty

which crowns the valley of fat -

a fresh-ripe fig in late spring,

no sooner picked than gobbled up.

On that day the Lord of Hosts will be

the glorious crown, the crowning beauty

of his people, the survivors.

(from Amos 3, 6, 9; Isaiah 28:1-5)

The prophets’ faith blinded them to the truth that Israel faced the best military machine ever created and stood no chance against it. It seems that they exaggerated the sins of Israel and Judah to explain their ruin. (Job’s comforters assume likewise that his sufferings are proof of sin.) Yet, if moral decline had indeed set in, to what extent was this caused or affected by the Assyrian threat? Could the abandonment of God have signified that Israel felt itself abandoned by God? (Israel’s turn from Yahweh to foreign gods in its final years is seen in the Nimrud Prism of Sargon II: on capturing Samaria, Sargon carried away ‘the gods in whom they trusted’ (Thomas, p. 60).) Also, if Israel had been firmer morally, would the military outcome have been different? These are not questions which the prophets ask. Certain that Israel was evil, they did not think of causes and motives. To them Israel had abandoned her faithful husband and become a whore. The most powerful use of this metaphor is made by Hosea, whose personal life intertwined with his prophetic vision to become a national symbol. His marriage to a prostitute who bore him three children - to whom he gave the symbolic names of Jezreel, ‘Not my People’ and ‘Unpitied’ - is an ugly microcosm of Yahweh’s stormy ‘marriage’ to Israel, an adulteress punished by divorce and exile. Yet Hosea’s dark curses and violent condemnation of Israel are mixed with rare tenderness, drawing upon metaphors of wasteland and fruitfulness, and culminating in the picture of a baby taught by its father to walk. Divine love triumphs over fury and brings an effusion of hope for salvation and return.

THE PROSTITUTION OF ISRAEL

Share not, Israel,

the joy of the nations!

You’ve gone a-whoring from your God,

on every granary floor

loosed your love for hire . . .

So the grain will fail them,

the new wine play them false.

Back to Egypt Ephraim will be driven:

Up to Asshur, to lead a filthy life -

No longer live in Yahweh’s land,

nor offer wine to please him.

Their sacrifices burn for themselves alone,

like the meat of mourners,

polluting those who eat it -

for they are not burnt in Yahweh’s temple.

(What will you do on the holy days, the days of Yahweh’s feast?)

Look! How they go, fugitives, plundered -

Egypt will heap them up.

Noph will bury them.

Their priceless silver will gather nettles.

Thorns will cover their tents

These are the days of reckoning,

these the days when scores are settled,

when Israel will know

for its sins

which prophet was a fool

and which was mad,

and why hatred has increased . . .

‘Yet, when I found Israel -

it was like grapes in the desert.

Your fathers were like first-ripe fruit.

Then they bowed to Ba’al Peor,

to the shame of Boshet.

They stank like the gods they loved.

Once Ephraim was firm as Tyre

a palm by an oasis . . .

Now he carries his sons to the slaughter!’

Give them, Lord . . . what will you

give them?

Give them

A womb that loses its babies,

and shrivelled breasts . . .

‘I will drive them from my house!’

‘I will not love them any more!’

Once Israel was a vine

bursting with fruit:

As his fruit increased, so did his altars.

The better his land,

the better his pillars -

Their love was split.

Now they bear the guilt.

Yahweh will break their altars,

knock down their pillars . . .

‘Ephraim is beaten

his root dried up.

He will bear no fruit -

If they raise sons,

I will bereave them, every one!’

My God . . . will turn his back on them.

They will be tramps among nations.

[Figure 5. Judean exiles from Lachish, 701 BC]

‘Yet - I taught Ephraim to walk,

holding them by the arms.

They didn’t know when I healed them.

I drew them to me with human bonds,

the cords of love,

easing the yoke off their jaws,

feeding them with care . . .

How can I give you up, Ephraim?

How can I make you like Admah and

Zeboim?

My heart burns with pity.

I will not follow my fury

to ruin Ephraim,

for I am God, not man.

I am holy inside you.

I need not breach the city walls!’

Those who walk behind the Lord

shall roar like a lion

for he will roar:

‘Let my sons come trembling

from the river lands . . .

Trembling like a bird from Egypt

and a dove from Asshur -

I will return them to their homes!’

(from Hosea 9, 10, 11)

Under Tiglath Pileser III, the Assyrians went to war, defeating Urartu in the north, subduing and annexing most of Aram, imposing vassal status on western kingdoms in southern Anatolia, Phoenicia, Transjordan and Philistia to the Egyptian border, and conquering Babylonia which had rebelled in the south-east. Israel and Judah were affected by this, the most extraordinary military feat in history to date, long before they were overrun. There were swift, violent changes in Israel: Zecharia, the last king of the Jehu dynasty, was murdered; his assassin, Shallum, was killed a month later by Menahem; Menahem held the Assyrians off by paying them tribute, but his son, Pekahiah, was murdered by Pekah who, in turn, was struck down by Hoshea, the last, ill-fated king of Israel.

Anxiety at the Assyrian threat fills the prophecies of that time. Around 734, Rezin, king of Aram, joined Pekah in a war against Judah with the aim of forcing the reluctant Judeans to join a coalition against Assyria. According to II Kings 16 and II Chronicles 28, Ahaz, king of Judah, sacrificed his son (or children) as a burnt offering; some scholars think that he committed this act to propitiate Yahweh in this crisis. Ignoring Isaiah’s advice, he turned to Assyria for help. Assyria, with an eye on the trade routes along the eastern Mediterranean, was waiting for just such a pretext to intervene. Ahaz accepted the yoke of vassaldom, paying large tributes and adopting some of the cultic practices of the Arameans. The Assyrians paid him by resuming their attack on Aram, easing the pressure on Judah. By 732, Aram was defeated and the Assyrians began their descent into Israel. Within a short time, Israel too was an Assyrian vassal. Isaiah minced no words in depicting the kingdoms of Aram and Israel, echoing Assyrian records in which their ruin is compared to a natural disaster such as a flood or storm (Pritchard, p. 283).

AGAINST DAMASCUS

Damascus is a city no longer

but a gutted ruin . . .

Abandoned, the towns of Aroer

where sheep graze freely,

unafraid.

Ephraim will lose its fortresses,

Damascus its kingdom.

What’s left of Aram -

like Israel shrunk,

says the Lord of Hosts.

(Isaiah 17:1-3)

With Judah’s submission to Assyria, biblical prophecy reached its high point in the poetry of Isaiah, a potent blend of hard moralizing and tender lyricism, of theology and aesthetics, history and universal truth. Like most, if not all, prophetic poetry, it is done in free verse, though one section (Isaiah 5, 9-10) is linked with a hammer-blow series of refrains. Its power is virtually a linguistic match for Assyria’s military might, a rod of God’s fury. Undercurrents of unease run through this poetry: for example, Judah’s guilt at being an indirect party to Israel’s subjugation through its alliance with Assyria, and its need to justify Israel’s fall by denouncing the northern kingdom for abandoning Yahweh and his Law. There is palpable relief that Judah has not suffered the same fate - its position in hilly land off the coast and the trade routes made it less important and more defensible than Israel. Yet who was to say that Judah could avoid Israel’s fate, seeing that it too was morally rotten. All that remained constant to Isaiah was in the empire of the heart - truth, faith, justice.

SONG OF A VINEYARD

A song of a vineyard

I sing to my beloved.

He had a vineyard

in a fat, brown patch.

He cleared the rocks,

he dug the earth,

he planted the freshest vines.

He built a fence, a tower, a cellar . . .

He hoped to grow grapes,

but they turned out rotten.

Men of Jerusalem!

Citizens of Judah!

Judge

Between me and my vineyard:

What more could I do for it?

I hoped to grow grapes.

Why did they turn out rotten?

Now I’ll tell you what I will do to my vineyard:

I’ll snatch its hedge for burning,

smash its fence for trampling,

lay it waste, unpruned, unhoed,

strangled with briars and thorns;

And the clouds I’ll command -

no rain for it!

For the vineyard of Yahweh Zebaot

Is the house of Israel. The men of Judah,

the joy of his planting.

He hoped justice would grow,

but there was bloodshed.

He hoped for righteousness,

but all that came up was a cry.

The Lord let fly this word to Israel

that all the nation should know -

even Ephraim and the men of Shomron, who say

with puffed-up hearts:

‘Though the bricks have fallen,

we’ll build again with cut stone.

To replace felled sycamores, we’ll plant cedars’ -

that Yahweh will rouse Rezin’s foes,

and stir Asshur to war -

Aram from the east, Philistines from the west,

to swallow Israel.

And still his anger burns,

his hand stretched out.

Hoi!

Asshur, rod of my wrath!

My fury a stave in his fist!

I cast him at a deceitful nation

to kill and to spoil,

to stamp him like mud in the streets!

And still this nation won’t repent

to the hammering God.

Yahweh Zebaot they seek not . . .

Their leaders bring them to the jaws of ruin.

The Lord will have no joy in his young men,

nor pity his orphans and widows -

for the nation is wicked to the core,

fool’s talk in the mouth of all . . .

And still his anger burns,

his hand stretched out.

Woe to those who make bad laws,

Who write injustice

to twist law from the poor,

rob them of their rights -

widows their prey, orphans their spoil!

What will you do on the day of judgement,

the ruin coming from a distance?

Where will you run for help?

Where will you hide your wealth?

What will you do,

but crouch among the captives,

cower among the slain.

And still his anger burns,

his hand stretched out.

Figure 6. Assyrian attack on a river town, c. 865

Woe to those who call bad good

and good bad,

make darkness light

and the light dark,

make sweet bitter

and the bitter sweet!

Woe to those who think they’re wise,

clever in their own eyes!

Woe to those who wake at dawn

to chase liquor, lingering after dark

for wine to inflame them!

Who feast on the harp, the psaltery,

the tabret and flute,

and wine.

Hoi!

Valorous drinkers!

Drunk - with the bribes of the wicked,

cheating good men of justice!

So, they will be as straw to fire.

Their root will turn rotten.

Their flower will turn to dust.

They loathed the law of Yahweh Zebaot,

cursed the word of Kedosh Yisrael.

This is why Yahweh is angry with his people.

He stretched out his hand and struck.

The hills shook.

Corpses fill the streets like dung.

And still his anger burns,

his hand stretched out?

(from Isaiah 5, 9, 10, 11)

The compensatory element of prophetic poetry is especially clear in Isaiah: Judah was weak militarily, but in the empire of faith it had the power of supreme rule. Yet for all its rhetorical force, this poetry has human frailty for its theme. Against the background of Assyria’s drive southward, Yahweh is depicted as a cuckolded husband or a disappointed father, betrayed and uncomprehending, full of lust for revenge. In this crisis, the prophets hark back to the idealized early years of Yahweh’s ‘marriage’ to Israel and to the happy ‘childhood’ of the nation. The importance of this mythologized history seems to have grown in proportion to the severity of the military threat. The prophets tried, in effect, to buttress crumbling national identity by asserting what seemed, in their view, firm, unchanging and unique in the Israelite tradition.

Micah, for example, affirms the wilderness bond between Yahweh and Israel. He sums up the essential moral principles on which the bond is based. The chaos and injustice of the present, he declares, might be undone by taking Israel’s ‘case’ to the most powerful symbols of permanence and order - the mountains. The mountains will confirm the endurance of Yahweh’s covenant, and the justice preserving it.

Perhaps only a nation like Judah, frequently under severe political and military pressure, could produce holy men and poets with so fine-tuned a sense of justice as Micah. To some later prophets, such as Ezekiel and Haggai, Temple ritual was of primary importance. But in general, the prophets emphasize moral principles and qualities of character, rather than power and the trappings of faith such as sacrifices. Yahweh’s demands are stated succinctly at the end of the following poem in the book of Micah.

THE COLLAPSE OF ISRAEL

Allelai!

No good men are left!

Each hunts the other, with nets.

Son abuses father,

daughter her mother and mother-in-law . . .

Man’s foes - his own family!

Hear - you mountains!

firm, rocky foundations of the earth:

Decide

Yahweh’s quarrel with his people . . .

My people! What have I done

to make you weary of me?

Answer!

I freed you from slavery in Egypt!

I sent Moses, Aaron and Miriam . . .

My people! Remember

the king of Moab, Balak’s plot - and the speech

of Balaam ben Peor - then, from Shittim to Gilgal,

the crossing into the land of Israel!

Remember the acts of Yahweh!

And if you ask:

How shall I come to Yahweh

and bow to him?

Shall I come with burnt-offerings,

with year-old calves?

Will God want rams by the thousand,

and rivers of oil?

Shall I sacrifice my first-born son

to atone for my sin?

Man - he’s told you what is good!

What does Yahweh want of you?

Only to do justice,

to love kindness,

to go humbly with your God . . .

(from Micah 6, 7)

Justice, kindness, modesty - words which may have had a bitterly ironic ring under Assyrian rule - might also have been used as code-words for revolt. No prophet seems to have called for armed revolt, knowing it to be futile. Yet the moral principles of Yahweh-worship, as well as many of the rituals and customs of the Israelites, were unlike those of Assyria and went side by side with political independence. Religious suppression, even if it appeared to be voluntary, was a psychological part of their political servitude. The submission of Israel and Judah to imperial power seems always to have been forced by necessity, and at virtually every sign of serious weakness in the empire, they rebelled. As we have seen, following the death of Tiglath Pileser III in 727, Israel revolted but was defeated, and after a siege of three years, Samaria fell in 721. A large number of the Israelites were deported to northern Mesopotamia and to Media beyond the Tigris river, where their national identity faded. Israel thus became an Assyrian province, renamed Samaria, and was repopulated with Babylonians, Arameans and others.

The Judean prophets’ fierce insistence on purity in faith was linked to Israel’s annihilation. For apart from its land, all that Judah had that was uniquely its own, generating unity, purpose and the potential for survival, was its faith. Weak faith was equal to weak national identity. With the loss of faith, the ten tribes of Israel lost their land and identity, and the prophets raged at their surviving people like a father trying to protect his endangered child.

Judah did not take part in Israel’s revolt and was spared deportation. The Judeans paid for survival with tribute and assimilation; shadowed by Israel’s fate, they had little choice but to submit to the Assyrians, though it is not clear whether or to what extent Ahaz’s adoption of pagan customs was forced or voluntary.

In the next few years, however, Assyria tired itself with campaigns against Phoenicia, Aram, Egypt, Elam, and most important of all, briefly lost control of Babylonia in a revolt led by Merodach Baladan (721-710). Many, if not all, the prophecies in Isaiah to the nations are responses to these wars, which went on annually during the rule of Sargon II. These prophecies - such as the ones on Tyre, Philistia, Moab, Arabia, Ethiopia, Egypt and Babylon - give a clear picture of the scope of Assyrian conquests and their impact on the Near East. In fact, though, Assyria is rarely mentioned by name: instead, the upheavals are ascribed to a northern power, an anonymous plunderer, a sword and bow, a hard master, or directly to God. The subjugation of Tyre, for example, was one of Assyria’s key victories, for it gave Assyria control over a vital link in the Mediterranean trade routes. It also enhanced Assyria’s prestige as the military superpower of its time: Tyre’s location on a rock island off the coast made it almost impregnable, but it was forced to submit and to pay tribute. This and other victories also consolidated Assyria’s status as the richest nation in the world, and the fruits of this victory appeared in the magnificent capitals of Khorsabad and Nineveh built within the next three decades. Yet Isaiah ascribes Tyre’s fall not to the Assyrian army but to God. The terse envoi is a sketch of Tyre seventy years later - a once-forgotten whore restored to wealth and power.

TYRE’S FATE

Howl! ships of Tarshish

for your homes are plundered!

Dumbstruck is Cyprus

and the Mediterranean coast,

once full of Zidon’s merchants,

trading in Egyptian grain,

harvest of the Nile -

for Tyre was market of nations . . .

Despair, Zidon! for the sea-fortress said:

I was never in labour,

I never gave birth,

I never raised

your young men and women . . .

The news will terrify Egypt.

Howl! men of Tyre:

Take refuge in Tarshish!

Is this your good-time town of old,

settling foreign lands?

Who brought this on Tyre,

Phoenicia’s crown,

whose traders were princes,

salt of the earth?

God of Hosts has done this

to pierce their pride,

to mock these honourable men.

Pour from your land like the Nile,

people of Tarshish: your harbour is gone,

nothing holds you there.

God has struck the sea,

shaken kingdoms, commanded the ruin

of Canaan’s fortresses.

Howl! ships of Tarshish

for your homes are plundered!

Envoi: Whore’s Song

take harp

circle city

forgotten whore

play well

sing much

be remembered

(Isaiah 23:1-11, 14, 16)

Another vital link in the chain of nations on the eastern side of the Fertile Crescent was Philistia, in the coastal lowlands west and southwest of Judah. In the confusion of the war waged against Judah by Israel and Aram (734-732), the Philistines (like the Edomites) had invaded Judean territory, and gave Ahaz a further motive for seeking Assyrian protection. Unlike Judah, which paid the Assyrians tribute, the Philistines tried to resist Assyrian rule and were overrun. As a longtime enemy of Philistia as well as a subject state of Assyria, Judah was hated by the Philistines, and Ahaz’s death (c. 720) set off rejoicing in Philistia. Isaiah’s poem, which dates from the year of Ahaz’s death, is a warning of Philistia’s impending doom and an assertion of Judah’s God-given power.

AGAINST PHILISTIA

Rejoice not, Philistia,

that the enemy-king is dead -

broken the rod that broke you -

for the snake will breed a viper,

its seed - a flying serpent.

While the poor earn their bread,

sleep safe, lamb-like,

your nobles I will starve.

The rest will be killed.

Howl, gate!

Cry, city!

Philistia, melt away,

for a smoke-cloud gathers

from the north . . .

And what shall be said

to the messengers of the nations?

That God has made Zion strong!

There the poor will shelter . . .

(Isaiah 14:29-32)

Judah’s relations with Moab, to the west, were better than those with Philistia and, judging from the only surviving relic of the Moabite language, on the Moabite Stone (discovered in 1868), Moab had a language and, presumably, a culture very similar to Judah’s (Thomas, pp. 195ff). Moab’s defeat by Assyria called up the following dirge by Isaiah in which criticism of the arrogance traditionally attributed to Moab is offset by poignant empathy, which may have been roused by Moabite refugees in Judah.

DIRGE FOR MOAB

Send a messenger to Judah’s king

from the desert-crags to Mount Zion -

for the Moabites flee like scattered birds

to the Arnon crossing:

‘Tell us what to do!

Make us a plan! Hide us!

Don’t give us away!

Give our exiles a home!

Protect Moab from the plunderer!

for Judah is rid of plunder and extortion,

its oppressor is gone!

And Judah’s throne is built on mercy,

its king rules by truth,

seeks justice - acts quickly!’

* * *

We have heard of Moab’s pride,

its overweening pride,

its wrath and lies -

So Moab will bewail itself,

every part of it -

for the grapes of Kir-hareseth,

bitter grief . . .

the vines of Heshbon are faded

and the vines of Sibmah,

intoxicator of kings,

whose tendrils stretched over the border

to Ya’azer, wandered through the desert across the Dead Sea.

Therefore I weep

the tears of Ya’azer,

the vines of Sibmah,

weep bitterly for Heshbon and Elaleh,

for the battle cry

has ended your harvest . . .

(Isaiah 16:1-9)

Other poems of Isaiah’s to the nations include one to Arabia, also subjugated by Assyria, and the mysterious oracle to Dumah, which is both the name of a place in the Arabian peninsula and the Hebrew word for silence.

ORACLES ON ARABIA

Sleep in the wilds of Arabia,

fugitive caravans of Dedan!

Give water to these thirsty men!

The Temites brought them bread,

these men who fled the sword,

the outdrawn sword, the outstretched bow,

fled the heavy war . . .

[Figure 7. Assyrian soldiers in pursuit of Arabs, c. 645 BC]

An oracle of silence:

A voice calls me from Seir:

Watchman, how far to dawn?

Watchman!

How far to dawn?

The watchman said:

Dawn comes, night too:

If you want, ask -

come back,

come . . .

(Isaiah 21:13-15, 11-12)

Assyria’s two main enemies, Egypt and Babylonia, lying at opposite ends of the Fertile Crescent, were the greatest prizes in its wars, and the control of these farflung territories tested Assyria’s imperial power and cohesion. Egypt, being further away, was the harder military and administrative challenge. Eventually, however, it was subdued, though not yet defeated, by Sargon II, who transferred an Assyrian population to Egypt and forced Egypt to trade with Assyria. Egypt’s attempts to stave off the Assyrians through magic are depicted graphically in Isaiah. Again, the Assyrians go unmentioned and the true author of these momentous events is Yahweh.

POEMS TO EGYPT AND ETHIOPIA

Here comes Yahweh on a cloud

swiftly riding into Egypt,

whose idols will shudder,

whose heart will melt -

I will set Egypt against Egypt,

brother will fight brother,

city against city, kingdom against kingdom:

Egypt’s spirit will be punctured,

They will go to idols,

to spirits of the dead,

to sorcerers and necromancers . . .

But I will turn Egypt over

to hard masters.

A cruel king will rule them,

says the Lord God of Hosts!

The Nile delta will go dry,

the river too,

boat and fish will vanish,

the arms of the Nile will sink and shrivel,

rush and reed will wither.

The naked Nile and banks of the Nile