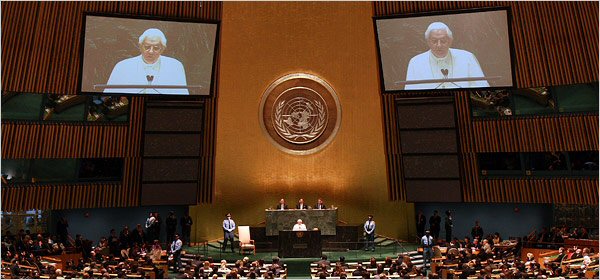

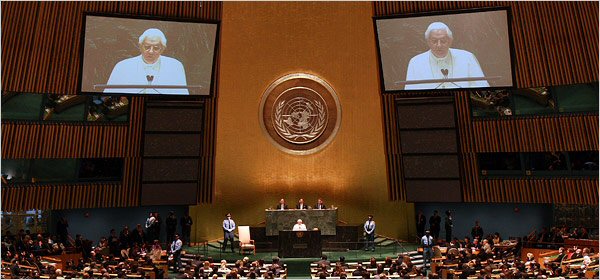

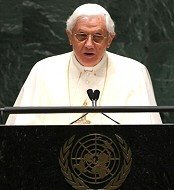

APOSTOLIC JOURNEY

TO THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AND VISIT TO THE UNITED NATIONS

ORGANIZATION HEADQUARTERS

MEETING WITH THE MEMBERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY

OF THE UNITED NATIONS ORGANIZATION

New York

Friday, 18 April 2008

Introduction

Governing the Human Family

Technology, Life and the Environment

International Intervention and the 'responsibility to protect'

Guarding the International Order's objective foundations

Human Rights and Relativism

Legality vs Justice

'Discernment' and Religion

Inter-religious Dialogue

Religious Freedom

Holy See's Role in International Relations

Greeting

Monsieur le Président,

Mesdames et Messieurs,

En m’adressant à cette Assemblée, j’aimerais avant tout vous exprimer, Monsieur le Président, ma vive reconnaissance pour vos aimables paroles. Ma gratitude va aussi au Secrétaire général, Monsieur Ban Ki-moon, qui m’a invité à venir visiter le Siège central de l’Organisation, et pour l’accueil qu’il m’a réservé. Je salue les Ambassadeurs et les diplomates des Pays membres et toutes les personnes présentes. À travers vous, je salue les peuples que vous représentez ici. Ils attendent de cette institution qu’elle mette en œuvre son inspiration fondatrice, à savoir constituer un « centre pour la coordination de l’activité des Nations unies en vue de parvenir à la réalisation des fins communes » de paix et de développement (cf. Charte des Nations unies, art. 1.2-1.4). Comme le Pape Jean-Paul II l’exprimait en 1995, l’Organisation devrait être un « centre moral, où toutes les nations du monde se sentent chez elles, développant la conscience commune d’être, pour ainsi dire, une famille de nations » (Message à l’Assemblée générale des Nations unies pour le 50e anniversaire de la fondation, New York, 5 octobre 1995).

À travers les Nations unies, les États ont établi des objectifs universels qui, même s’ils ne coïncident pas avec la totalité du bien commun de la famille humaine, n’en représentent pas moins une part fondamentale. Les principes fondateurs de l’Organisation – le désir de paix, le sens de la justice, le respect de la dignité de la personne, la coopération et l’assistance humanitaires – sont l’expression des justes aspirations de l’esprit humain et constituent les idéaux qui devraient sous-tendre les relations internationales. Comme mes prédécesseurs Paul VI et Jean-Paul II l’ont affirmé depuis cette même tribune, tout cela fait partie de réalités que l'Église Catholique et le Saint-Siège considèrent avec attention et intérêt, voyant dans votre activité un exemple de la manière dont les problèmes et les conflits qui concernent la communauté mondiale peuvent bénéficier d’une régulation commune. Les Nations unies concrétisent l’aspiration à « un degré supérieur d’organisation à l’échelle internationale » (Jean-Paul II, Encycl. Sollicitudo rei socialis, n. 43), qui doit être inspiré et guidé par le principe de subsidiarité et donc être capable de répondre aux exigences de la famille humaine, grâce à des règles internationales efficaces et à la mise en place de structures aptes à assurer le déroulement harmonieux de la vie quotidienne des peuples. Cela est d’autant plus nécessaire dans le contexte actuel où l’on fait l’expérience du paradoxe évident d’un consensus multilatéral qui continue à être en crise parce qu’il est encore subordonné aux décisions d’un petit nombre, alors que les problèmes du monde exigent, de la part de la communauté internationale, des interventions sous forme d’actions communes.

En effet, les questions de sécurité, les objectifs de développement, la réduction des inégalités au niveau local et mondial, la protection de l’environnement, des ressources et du climat, requièrent que tous les responsables de la vie internationale agissent de concert et soient prêts à travailler en toute bonne foi, dans le respect du droit, pour promouvoir la solidarité dans les zones les plus fragiles de la planète. Je pense en particulier à certains pays d’Afrique et d’autres continents qui restent encore en marge d’un authentique développement intégral, et qui risquent ainsi de ne faire l’expérience que des effets négatifs de la mondialisation. Dans le contexte des relations internationales, il faut reconnaître le rôle primordial des règles et des structures qui, par nature, sont ordonnées à la promotion du bien commun et donc à la sauvegarde de la liberté humaine. Ces régulations ne limitent pas la liberté. Au contraire, elles la promeuvent quand elles interdisent des comportements et des actions qui vont à l’encontre du bien commun, qui entravent son exercice effectif et qui compromettent donc la dignité de toute personne humaine. Au nom de la liberté, il doit y avoir une corrélation entre droits et devoirs, en fonction desquels toute personne est appelée à prendre ses responsabilités dans les choix qu’elle opère, en tenant compte des relations tissées avec les autres. Nous pensons ici à la manière dont les résultats de la recherche scientifique et des avancées technologiques ont parfois été utilisés. Tout en reconnaissant les immenses bénéfices que l’humanité peut en tirer, certaines de leurs applications représentent une violation évidente de l’ordre de la création, au point non seulement d’être en contradiction avec le caractère sacré de la vie, mais d’arriver à priver la personne humaine et la famille de leur identité naturelle. De la même manière, l’action internationale visant à préserver l’environnement et à protéger les différentes formes de vie sur la terre doit non seulement garantir un usage rationnel de la technologie et de la science, mais doit aussi redécouvrir l’authentique image de la création. Il ne s’agira jamais de devoir choisir entre science et éthique, mais bien plutôt d’adopter une méthode scientifique qui soit véritablement respectueuse des impératifs éthiques.

La reconnaissance de l’unité de la famille humaine et l’attention portée à la dignité innée de toute femme et de tout homme reçoivent aujourd’hui un nouvel élan dans le principe de la responsabilité de protéger. Il n’a été défini que récemment, mais il était déjà implicitement présent dès les origines des Nations unies et, actuellement, il caractérise toujours davantage son activité. Tout État a le devoir primordial de protéger sa population contre les violations graves et répétées des droits de l’homme, de même que des conséquences de crises humanitaires liées à des causes naturelles ou provoquées par l’action de l’homme. S’il arrive que les États ne soient pas en mesure d’assurer une telle protection, il revient à la communauté internationale d’intervenir avec les moyens juridiques prévus par la Charte des Nations unies et par d’autres instruments internationaux. L’action de la communauté internationale et de ses institutions, dans la mesure où elle est respectueuse des principes qui fondent l’ordre international, ne devrait jamais être interprétée comme une coercition injustifiée ou comme une limitation de la souveraineté. À l’inverse, c’est l’indifférence ou la non-intervention qui causent de réels dommages. Il faut réaliser une étude approfondie des modalités pour prévenir et gérer les conflits, en utilisant tous les moyens dont dispose l’action diplomatique et en accordant attention et soutien même au plus léger signe de dialogue et de volonté de réconciliation.

Le principe de la « responsabilité de protéger » était considéré par l’antique ius gentium comme le fondement de toute action entreprise par l’autorité envers ceux qui sont gouvernés par elle : à l’époque où le concept d’État national souverain commençait à se développer, le religieux dominicain Francisco De Vitoria, considéré à juste titre comme un précurseur de l’idée des Nations unies, décrivait cette responsabilité comme un aspect de la raison naturelle partagé par toutes les nations, et le fruit d’un droit international dont la tâche était de réguler les relations entre les peuples. Aujourd’hui comme alors, un tel principe doit faire apparaître l’idée de personne comme image du Créateur, ainsi que le désir d’absolu et l’essence de la liberté. Le fondement des Nations unies, nous le savons bien, a coïncidé avec les profonds bouleversements dont a souffert l’humanité lorsque la référence au sens de la transcendance et à la raison naturelle a été abandonnée et que par conséquent la liberté et la dignité humaine furent massivement violées. Dans de telles circonstances, cela menace les fondements objectifs des valeurs qui inspirent et régulent l’ordre international et cela mine les principes intangibles et coercitifs formulés et consolidés par les Nations unies. Face à des défis nouveaux répétés, c’est une erreur de se retrancher derrière une approche pragmatique, limitée à mettre en place des « bases communes », dont le contenu est minimal et dont l’efficacité est faible.

La référence à la dignité humaine, fondement et fin de la responsabilité de protéger, nous introduit dans la note spécifique de cette année, qui marque le soixantième anniversaire de la Déclaration universelle des Droits de l’homme. Ce document était le fruit d’une convergence de différentes traditions culturelles et religieuses, toutes motivées par le désir commun de mettre la personne humaine au centre des institutions, des lois et de l’action des sociétés, et de la considérer comme essentielle pour le monde de la culture, de la religion et de la science. Les droits de l’homme sont toujours plus présentés comme le langage commun et le substrat éthique des relations internationales. Tout comme leur universalité, leur indivisibilité et leur interdépendance sont autant de garanties de protection de la dignité humaine. Mais il est évident que les droits reconnus et exposés dans la Déclaration s’appliquent à tout homme, cela en vertu de l’origine commune des personnes, qui demeure le point central du dessein créateur de Dieu pour le monde et pour l’histoire. Ces droits trouvent leur fondement dans la loi naturelle inscrite au cœur de l’homme et présente dans les diverses cultures et civilisations. Détacher les droits humains de ce contexte signifierait restreindre leur portée et céder à une conception relativiste, pour laquelle le sens et l’interprétation des droits pourraient varier et leur universalité pourrait être niée au nom des différentes conceptions culturelles, politiques, sociales et même religieuses. La grande variété des points de vue ne peut pas être un motif pour oublier que ce ne sont pas les droits seulement qui sont universels, mais également la personne humaine, sujet de ces droits.

The life of the community, both domestically and internationally, clearly demonstrates that respect for rights, and the guarantees that follow from them, are measures of the common good that serve to evaluate the relationship between justice and injustice, development and poverty, security and conflict. The promotion of human rights remains the most effective strategy for eliminating inequalities between countries and social groups, and for increasing security. Indeed, the victims of hardship and despair, whose human dignity is violated with impunity, become easy prey to the call to violence, and they can then become violators of peace. The common good that human rights help to accomplish cannot, however, be attained merely by applying correct procedures, nor even less by achieving a balance between competing rights. The merit of the Universal Declaration is that it has enabled different cultures, juridical expressions and institutional models to converge around a fundamental nucleus of values, and hence of rights. Today, though, efforts need to be redoubled in the face of pressure to reinterpret the foundations of the Declaration and to compromise its inner unity so as to facilitate a move away from the protection of human dignity towards the satisfaction of simple interests, often particular interests. The Declaration was adopted as a "common standard of achievement" (Preamble) and cannot be applied piecemeal, according to trends or selective choices that merely run the risk of contradicting the unity of the human person and thus the indivisibility of human rights.

Experience shows that legality often prevails over justice when the insistence upon rights makes them appear as the exclusive result of legislative enactments or normative decisions taken by the various agencies of those in power. When presented purely in terms of legality, rights risk becoming weak propositions divorced from the ethical and rational dimension which is their foundation and their goal. The Universal Declaration, rather, has reinforced the conviction that respect for human rights is principally rooted in unchanging justice, on which the binding force of international proclamations is also based. This aspect is often overlooked when the attempt is made to deprive rights of their true function in the name of a narrowly utilitarian perspective. Since rights and the resulting duties follow naturally from human interaction, it is easy to forget that they are the fruit of a commonly held sense of justice built primarily upon solidarity among the members of society, and hence valid at all times and for all peoples. This intuition was expressed as early as the fifth century by Augustine of Hippo, one of the masters of our intellectual heritage. He taught that the saying: Do not do to others what you would not want done to you "cannot in any way vary according to the different understandings that have arisen in the world" (De Doctrina Christiana, III, 14). Human rights, then, must be respected as an expression of justice, and not merely because they are enforceable through the will of the legislators.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

As history proceeds, new situations arise, and the attempt is made to link them to new rights. Discernment, that is, the capacity to distinguish good from evil, becomes even more essential in the context of demands that concern the very lives and conduct of persons, communities and peoples. In tackling the theme of rights, since important situations and profound realities are involved, discernment is both an indispensable and a fruitful virtue.

Discernment, then, shows that entrusting exclusively to individual States, with their laws and institutions, the final responsibility to meet the aspirations of persons, communities and entire peoples, can sometimes have consequences that exclude the possibility of a social order respectful of the dignity and rights of the person. On the other hand, a vision of life firmly anchored in the religious dimension can help to achieve this, since recognition of the transcendent value of every man and woman favours conversion of heart, which then leads to a commitment to resist violence, terrorism and war, and to promote justice and peace. This also provides the proper context for the inter-religious dialogue that the United Nations is called to support, just as it supports dialogue in other areas of human activity. Dialogue should be recognized as the means by which the various components of society can articulate their point of view and build consensus around the truth concerning particular values or goals. It pertains to the nature of religions, freely practised, that they can autonomously conduct a dialogue of thought and life. If at this level, too, the religious sphere is kept separate from political action, then great benefits ensue for individuals and communities. On the other hand, the United Nations can count on the results of dialogue between religions, and can draw fruit from the willingness of believers to place their experiences at the service of the common good. Their task is to propose a vision of faith not in terms of intolerance, discrimination and conflict, but in terms of complete respect for truth, coexistence, rights, and reconciliation.

Human rights, of course, must include the right to religious freedom, understood as the expression of a dimension that is at once individual and communitarian – a vision that brings out the unity of the person while clearly distinguishing between the dimension of the citizen and that of the believer. The activity of the United Nations in recent years has ensured that public debate gives space to viewpoints inspired by a religious vision in all its dimensions, including ritual, worship, education, dissemination of information and the freedom to profess and choose religion. It is inconceivable, then, that believers should have to suppress a part of themselves – their faith – in order to be active citizens. It should never be necessary to deny God in order to enjoy one’s rights. The rights associated with religion are all the more in need of protection if they are considered to clash with a prevailing secular ideology or with majority religious positions of an exclusive nature. The full guarantee of religious liberty cannot be limited to the free exercise of worship, but has to give due consideration to the public dimension of religion, and hence to the possibility of believers playing their part in building the social order. Indeed, they actually do so, for example through their influential and generous involvement in a vast network of initiatives which extend from Universities, scientific institutions and schools to health care agencies and charitable organizations in the service of the poorest and most marginalized. Refusal to recognize the contribution to society that is rooted in the religious dimension and in the quest for the Absolute – by its nature, expressing communion between persons – would effectively privilege an individualistic approach, and would fragment the unity of the person.

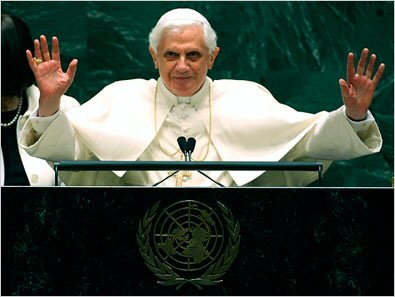

My presence at this Assembly is a sign of esteem for the United Nations, and it is intended to express the hope that the Organization will increasingly serve as a sign of unity between States and an instrument of service to the entire human family. It also demonstrates the willingness of the Catholic Church to offer her proper contribution to building international relations in a way that allows every person and every people to feel they can make a difference. In a manner that is consistent with her contribution in the ethical and moral sphere and the free activity of her faithful, the Church also works for the realization of these goals through the international activity of the Holy See. Indeed, the Holy See (Vatican) has always had a place at the assemblies of the Nations, thereby manifesting its specific character as a subject in the international domain. As the United Nations recently confirmed, the Holy See thereby makes its contribution according to the dispositions of international law, helps to define that law, and makes appeal to it.

The United Nations remains a privileged setting in which the Church is committed to contributing her experience "of humanity", developed over the centuries among peoples of every race and culture, and placing it at the disposal of all members of the international community. This experience and activity, directed towards attaining freedom for every believer, seeks also to increase the protection given to the rights of the person. Those rights are grounded and shaped by the transcendent nature of the person, which permits men and women to pursue their journey of faith and their search for God in this world. Recognition of this dimension must be strengthened if we are to sustain humanity’s hope for a better world and if we are to create the conditions for peace, development, cooperation, and guarantee of rights for future generations.

In my recent Encyclical, Spe Salvi, I indicated that "every generation has the task of engaging anew in the arduous search for the right way to order human affairs" (no. 25). For Christians, this task is motivated by the hope drawn from the saving work of Jesus Christ. That is why the Church is happy to be associated with the activity of this distinguished Organization, charged with the responsibility of promoting peace and good will throughout the earth. Dear Friends, I thank you for this opportunity to address you today, and I promise you of the support of my prayers as you pursue your noble task.

Before I take my leave from this distinguished Assembly, I should like to offer my greetings, in the official languages, to all the Nations here represented.

Peace and Prosperity with God’s help!

Paix et prospérité, avec l’aide de Dieu!

[ Return ]